Spaniards

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2016) |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Spain nationals 41,539,400[1] (for a total population of 47,059,533) Hundreds of millions of Hispanic Americans of full or partial Spanish ancestry[2][3][4][5][6][7] 840,535 were born in Spain 1,542,809 were born in the country of residence 265,885 others[9] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Spain 41,539,400 (2015)[1] | |

| Diaspora | |

| 404,111 (92,610 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 310,072 (240,153 born in Spain)[11][12][13][8][10] | |

| 192,766 (48,546 born in Spain)[14][8][10] | |

| 182,631 (61,881 born in Spain)[15][10][16][17] | |

| 181,181 (2020) (including de jure Spanish citizens that were not born in Spain)[18][19] | |

| 136,145 (30,167 born in Spain)[20] | |

| 117,523 (29,848 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 108,858 (2,114 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 108,314 (17,485 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 103,247 (46,947 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 63,827 (12,023 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 56,104 (9,669 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 53,212 (26,616 born in Spain)[21] | |

| 35,616 (13,120 born in Spain)[22] | |

| 30,683 (8,057 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 27,489 (4,028 born in Spain)[23] | |

| 24,485 (17,771 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 21,974 (12,406 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 20,898 (11,734 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 18,928 (3,622 born in Spain)[10][21] | |

| 18,353 (10,506 born in Spain)[8][10] | |

| 16,482[24] | |

| 15,390[25] | |

| 12,375[24] | |

| 12,000[26] | |

| 9,311[27] | |

| 8,003[10] | |

| 6,794[28] | |

| 5,000[29] | |

| 3,380[30] | |

| 3,110[31] | |

| ~ 1,000 (2009)[32] | |

| 2,450[24] | |

| 2,118–45,935[10][33] | |

| 1,826[34] | |

| 1,489[10] | |

| 1,007[10] | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish (see languages) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Catholic Christianity Minority Irreligion[35][36] | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Spanish people |

|---|

Rojigualda (historical Spanish flag) |

| Regional groups |

Other groups

|

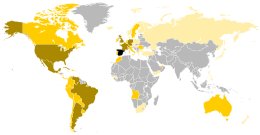

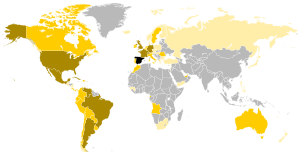

| Significant Spanish diaspora |

|

|

Spaniards,[a] or Spanish people, are a people native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of national and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex history, including a number of different languages, both indigenous and local linguistic descendants of the Roman-imposed Latin language, of which Spanish is the largest and the only one that is official throughout the whole country.

Commonly spoken regional languages include, most notably, the sole surviving indigenous language of Iberia, Basque, as well as other Latin-descended Romance languages like Spanish itself, Catalan and Galician. Many populations outside Spain have ancestors who emigrated from Spain and share elements of a Hispanic culture. The most notable of these comprise Hispanic America in the Western Hemisphere.

The Roman Republic conquered Iberia during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. Hispania, the name given to Iberia by the Romans as a province of their Empire, underwent a process of linguistic and cultural Romanization, and as such, the majority of local languages in Spain today, with the exception of Basque, evolved out of Vulgar Latin which was introduced by the ancient Romans. At the end of the Western Roman Empire, the Germanic tribal confederations migrated from Central Europe, invaded the Iberian Peninsula and established relatively independent realms in its western provinces, including the Suebi, Alans and Vandals. Eventually, the Visigoths would forcibly integrate all remaining independent territories in the peninsula, including the Byzantine province of Spania, into the Visigothic Kingdom, which more or less unified politically, ecclesiastically, and legally all the former Roman provinces or successor kingdoms of what was then documented as Hispania.

In the early eighth century, the Visigothic Kingdom was conquered by the Umayyad Islamic Caliphate that arrived to the peninsula in the year 711. The Muslim rule in the Iberian Peninsula, termed al-Andalus, soon became autonomous from Baghdad. The handful of small Christian pockets in the north left out of Muslim rule, along the presence of the Carolingian Empire near the Pyrenean range, would eventually lead to the emergence of the Christian kingdoms of León, Castile, Aragon, Portugal and Navarre. Along seven centuries, an intermittent southwards expansion of the latter kingdoms (known in historiography as the Reconquista) took place, culminating with the Christian seizure of the last Muslim polity (the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada) in 1492, the same year Christopher Columbus arrived in the New World. During the centuries after the Reconquista, the Christian kings of Spain persecuted and expelled ethnic and religious minorities such as Jews and Muslims through the Spanish Inquisition.[37]

A process of political conglomeration among the Christian kingdoms also ensued, and the late 15th-century saw the dynastic union of Castile and Aragon under the Catholic Monarchs, generally considered the point of emergence of Spain as a unified country. The Conquest of Navarre occurred in 1512. There was also a period called Iberian Union, the dynastic union of the Kingdom of Portugal and the Spanish Crown; during which, both countries were ruled by the Spanish Habsburg kings between 1580 and 1640.

In the early modern period, Spain had one of the largest empires in history, which was also one of the first global empires, leaving a large cultural and linguistic legacy that includes over 570 million Hispanophones,[38] making Spanish the world's second-most spoken native language, after Mandarin Chinese. During the Golden Age there were also many advancements in the arts, with the rise of renowned painters such as Diego Velázquez. The most famous Spanish literary work, Don Quixote, was also published during the Golden Age of the Spanish Empire.

The population of Spain has become more diverse due to immigration of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. From 2000 to 2010, Spain had among the highest per capita immigration rates in the world and the second-highest absolute net migration in the world (after the United States).[39] The diverse regional and cultural populations mainly include the Castilians, Aragonese, Catalans, Andalusians, Valencians, Balearics, Canarians, Basques and the Galicians among others.

History

Early populations

The earliest modern humans inhabiting the region of Spain are believed to have been Paleolithic peoples, who may have arrived in the Iberian Peninsula as early as 35,000–40,000 years ago. The Iberians are believed to have arrived or emerged in the region as a culture between the 4th millennium BC and the 3rd millennium BC, settling initially along the Mediterranean coast.[citation needed]

Then Celts settled in Spain during the Iron Age. Some of those tribes in North-central Spain, who had cultural contact with the Iberians, are called Celtiberians. In addition, a group known as the Tartessians and later Turdetanians inhabited southwestern Spain. They are believed to have developed a separate culture influenced by Phoenicia. The seafaring Phoenicians,[40] Greeks, and Carthaginians successively settled trading colonies along the Mediterranean coast over a period of several centuries. Interaction took place with Indigenous peoples. The Second Punic War between the Carthaginians and Romans was fought mainly in what is now Spain and Portugal.[41]

The Roman Republic conquered Iberia during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, and established a series of Latin-speaking provinces in the region. As a result of Roman colonization, the majority of local languages, with the exception of Basque, stem from the Vulgar Latin that was spoken in Hispania (Roman Iberia). A new group of Romance languages of the Iberian Peninsula including Spanish, which eventually became the main language in Spain evolved from Roman expansion. Hispania emerged as an important part of the Roman Empire and produced notable historical figures such as Trajan, Hadrian, Seneca, Martial, Theodosius, and Quintilian.

The Germanic Vandals and Suebi, with Iranian Alans under King Respendial, arrived in the peninsula in 409 AD. Part of the Vandals with the remaining Alans, now under Geiseric, removed to North Africa after a few conflicts with another Germanic tribe, the Visigoths. The latter were established in Toulouse and supported Roman campaigns against the Vandals and Alans in 415–19 AD.

The Visigoths became the dominant power in Iberia and reigned for three centuries. They were highly romanized in the eastern Empire and already Christians, so they became fully integrated into the late Iberian-Roman culture.

The Suebi were another Germanic tribe in the west of the peninsula; some sources said that they became established as federates of the Roman Empire in the old Northwestern Roman province of Gallaecia (roughly, present-day northern Portugal and Galicia). But they were largely independent and raided neighboring provinces to expand their political control over ever-larger portions of the southwest after the Vandals and Alans left. They created a totally independent Suebic Kingdom. In 447 AC they converted to Roman Catholicism under King Rechila.

After being checked and reduced in 456 AD by the Visigoths, the Suebic Kingdom survived to 585 AD. It was decimated as an independent political unit by the Visigoths, after having been involved in the internal affairs of their kingdom.

Middle Ages

After two centuries of domination by the Visigothic Kingdom, the Iberian Peninsula was invaded by a Muslim force under Tariq Bin Ziyad in 711. This army consisted mainly of ethnic Berbers from the Ghomara tribe, who were reinforced by Arabs from Syria once the conquest was complete. Only a remote mountainous area in the far north retained independence, eventually developing as the Christian Kingdom of Asturias.

Muslim Iberia became part of the Umayyad Caliphate and would be known as Al-Andalus. The Berbers of Al Andalus revolted as early as 740 AD, halting Arab expansion across the Pyrenee Mountains into France. Upon the collapse of the Umayyad in Damascus, Spain was seized by Yusuf al Fihri. The exiled Umayyad Prince Abd al-Rahman I next seized power, establishing himself as Emir of Cordoba. Abd al Rahman III, his grandson, proclaimed a Caliphate in 929, marking the beginning of the Golden Age of Al Andalus. This policy was the effective power of the peninsula and Western North Africa; it competed with the Shiite rulers of Tunis and frequently raided the small Christian kingdoms in the North.

The Caliphate of Córdoba effectively collapsed during a ruinous civil war between 1009 and 1013; it was not finally abolished until 1031, when al-Andalus broke up into a number of mostly independent mini-states and principalities called taifas. These were generally too weak to defend themselves against repeated raids and demands for tribute from the Christian states to the north and west, which were known to the Muslims as "the Galician nations". These had expanded from their initial strongholds in Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, the Basque country, and the Carolingian Marca Hispanica to become the Kingdoms of Navarre, León, Portugal, Castile and Aragon, and the County of Barcelona. Eventually they began to conquer territory, and the Taifa kings asked for help from the Almoravids, Muslim Berber rulers of the Maghreb. But the Almoravids went on to conquer and annex all the Taifa kingdoms.

In 1086 the Almoravid ruler of Morocco, Yusuf ibn Tashfin, was invited by the Muslim princes in Iberia to defend them against Alfonso VI, King of Castile and León. In that year, Tashfin crossed the straits to Algeciras and inflicted defeat on the Christian army at the Battle of Sagrajas. By 1094, Yusuf ibn Tashfin had removed all Muslim princes in Iberia and had annexed their states, except for the one at Zaragoza. He also regained Valencia from the Christians. About this time a massive process of conversion to Islam took place, and Muslims comprised the majority of the population in Spain by the end of the 11th century.

The Almoravids were succeeded by the Almohads, another Berber dynasty, after the victory of Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur over the Castilian Alfonso VIII at the Battle of Alarcos in 1195. In 1212 a coalition of Christian kings under the leadership of the Castilian Alfonso VIII defeated the Almohads at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa. But the Almohads continued to rule Al-Andalus for another decade, though with much reduced power and prestige. The civil wars following the death of Abu Ya'qub Yusuf II rapidly led to the re-establishment of taifas. The taifas, newly independent but weakened, were quickly conquered by the kingdoms of Portugal, Castile, and Aragon. After the fall of Murcia (1243) and the Algarve (1249), only the Emirate of Granada survived as a Muslim state, tributary of Castile until 1492.

In 1469 the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile signaled a joining of forces to attack and conquer the Emirate of Granada. The King and Queen convinced the Pope to declare their war a crusade. The Christians were successful and finally, in January 1492, after a long siege, the Moorish sultan Muhammad XII surrendered the fortress palace, the renowned Alhambra.

Spain conquered the Canary Islands between 1402 and 1496. Their indigenous Berber population, the Guanches, were gradually absorbed by intermarrying with Spanish settlers.

Spanish conquest of the Iberian part of Navarre was begun by Ferdinand II of Aragon and completed by Charles V. The series of military campaigns extended from 1512 to 1524, while the war lasted until 1528 in the Navarre to the north of the Pyrenees. Between 1568 and 1571, Charles V armies fought and defeated a general insurrection of the Muslims of the mountains of Granada. Charles V then ordered the expulsion of up to 80,000 Granadans from the province and their dispersal throughout Spain.

The union of the Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragon as well as the conquest of Granada, Navarre and the Canary Islands led to the formation of the Spanish state as known today. This allowed for the development of a Spanish identity based on the Spanish language and a local form of Catholicism. This gradually developed in a territory that remained culturally, linguistically and religiously very diverse.

A majority of Jews were forcibly converted to Catholicism during the 14th and 15th centuries and those remaining were expelled from Spain in 1492. The open practice of Islam by Spain's sizeable Mudejar population was similarly outlawed. Furthermore, between 1609 and 1614, a significant number of Moriscos— (Muslims who had been baptized Catholic) were expelled by royal decree.[42] Although initial estimates of the number of Moriscos expelled such as those of Henri Lapeyre reach 300,000 moriscos (or 4% of the total Spanish population), the extent and severity of the expulsion has been increasingly challenged by modern historians. Nevertheless, the eastern region of Valencia, where ethnic tensions were highest, was particularly affected by the expulsion, suffering economic collapse and depopulation of much of its territory.

The Islamic legacy in Spain has been long lasting, and among many others, accounts for two of the eight masterpieces of Islamic architecture from around the world: the Alhambra of Granada and the Cordoba Mosque;[43] the Palmeral of Elche [44] is listed as a World Heritage Site due to its uniqueness.[45]

Those who avoided expulsion or who managed to return to Spain merged into the dominant culture.[46] The last mass prosecution against Moriscos for crypto-Islamic practices took place in Granada in 1727, with most of those convicted receiving relatively light sentences. By the end of the 18th century, Indigenous Islam and Morisco identity were considered to have been extinguished in Spain.[47]

Colonialism and emigration

In the 16th century, following the military conquest of most of the new continent, perhaps 240,000 Spaniards entered American ports. They were joined by 450,000 in the next century.[48] It is estimated that during the colonial period (1492–1832), a total of 1.86 million Spaniards settled in the Americas and a further 3.5 million immigrated during the post-colonial era (1850–1950); the estimate is 250,000 in the 16th century, and most during the 18th century as immigration was encouraged by the new Bourbon Dynasty. After the conquest of Mexico and Peru these two regions became the principal destinations of Spanish colonial settlers in the 16th century.[49] In the period 1850–1950, 3.5 million Spanish left for the Americas, particularly Argentina, Uruguay, Mexico,[citation needed] Brazil, Chile, Venezuela, and Cuba.[50] From 1840 to 1890, as many as 40,000 Canary Islanders emigrated to Venezuela.[51] 94,000 Spaniards chose to go to Algeria in the last years of the 19th century, and 250,000 Spaniards lived in Morocco at the beginning of the 20th century.[50]

By the end of the Spanish Civil War, some 500,000 Spanish Republican refugees had crossed the border into France.[52] From 1961 to 1974, at the height of the guest worker in Western Europe, about 100,000 Spaniards emigrated each year.[50] The nation has formally apologized to expelled Jews and since 2015 offers the chance for people to reclaim Spanish citizenship. By 2019, over 132,000 Sephardic Jewish descendants had reclaimed Spanish citizenship.[53][54]

The population of Spain has become more diverse due to immigration of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. From 2000 to 2010, Spain had among the highest per capita immigration rates in the world and the second-highest absolute net migration in the world (after the United States).[39] Immigrants now make up about 10% of the population. But Spain's prolonged economic crisis between 2008 and 2015 reduced economic opportunities, and both immigration rates and the total number of foreigners in the country declined. By the end of this period, Spain was becoming a net emigrant country.

Ancestry

Historical origins and genetics

Spanish people, like most Europeans, largely descend from three distinct lineages:[55] Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, descended from populations associated with the Paleolithic Epigravettian culture;[56] Neolithic Early European Farmers who migrated from Anatolia during the Neolithic Revolution 9,000 years ago;[57] and Yamnaya Steppe herders who expanded into Europe from the Pontic–Caspian steppe of Ukraine and southern Russia in the context of Indo-European migrations 5,000 years ago.[55]

The Spanish people's genetic pool largely derives from the pre-Roman inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula:

- Pre-Indo-European and Indo-European speaking pre-Celtic groups: (Iberians, Vettones, Turdetani, Aquitani).[58][59][60]

- Celts (Gallaecians, Celtiberians, Turduli and Celtici),[61][60] who were Romanized after the conquest of the region by the ancient Romans.[62][63]

There are also some genetic influences from Germanic tribes who arrived after the Roman period, including the Suebi, Hasdingi Vandals, Alans and Visigoths.[64][65][66] Due to its position on the Mediterranean Sea, like other Southern European countries, the land that is now Spain also had contact with other Mediterranean peoples such as the ancient Phoenicians, Greeks and Carthaginians who briefly settled along the Iberian Mediterranean coast, the Sephardi Jewish community, and Berbers and Arabs arrived during Al-Andalus, all of them leaving some North African and Middle Eastern genetic contributions, particularly in the Southern and Western Iberian Peninsula.[67][68][63][69][70][71][62]

Peoples of Spain

Nationalities and regions

Within Spain, there are various nationalities and regional populations including the Andalusians, Castilians, Catalans, Valencians and Balearics (who speak Catalan, a distinct Romance language in eastern Spain), the Basques (who live in the Basque country and north of Navarre and speak Basque, a non-Indo-European language), and the Galicians (who speak Galician, a descendant of old Galician-Portuguese).

Respect to the existing cultural pluralism is important to many Spaniards. In many regions there exist strong regional identities such as Asturias, Aragon, the Canary Islands, León, and Andalusia, while in others (like Catalonia, Basque Country or Galicia) there are stronger national sentiments. Many of them refuse to identify themselves with the Spanish ethnic group and prefer some of the following:

- Nationalities and regional identities

Romani minority

Spain is home to one of the largest communities of Romani people (commonly known by the English exonym "gypsies", Spanish: gitanos). The Spanish Roma, which belong to the Iberian Kale subgroup (calé), are a formerly-nomadic community, which spread across Western Asia, North Africa, and Europe, first reaching Spain in the 15th century.

Data on ethnicity is not collected in Spain, although the Government's statistical agency CIS estimated in 2007 that the number of Gitanos present in Spain is probably around one million.[72] Most Spanish Roma live in the autonomous community of Andalusia, where they have traditionally enjoyed a higher degree of integration than in the rest of the country. A number of Spanish Calé also live in Southern France, especially in the region of Perpignan.

Modern immigration

The population of Spain has become increasingly diverse due to recent immigration. From 2000 to 2010, Spain had among the highest per capita immigration rates in the world and the second highest absolute net migration in the World (after the United States)[39] and immigrants now make up about 10% of the population. Since 2000, Spain has absorbed more than 3 million immigrants, with thousands more arriving each year.[73] In 2008, the immigrant population topped over 4.5 million.[74] These immigrants came mainly from Europe, Latin America, Asia, North Africa, and West Africa.[75]

Languages

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

Languages spoken in Spain include Spanish (castellano or español) (74%), Catalan (català, called valencià, in the Valencian Community) (17%), Galician (galego) (7%), and Basque (euskara) (2%).[76] Other languages with a lower level of official recognition are Asturian (asturianu), Aranese Gascon (aranés), Aragonese (aragonés), and Leonese, each with their own various dialects. Spanish is the official state language, although the other languages are co-official in a number of autonomous communities.

Peninsular Spanish is typically classified in northern and southern dialects; among the southern ones Andalusian Spanish is particularly important. The Canary Islands have a distinct dialect of Spanish which is close to Caribbean Spanish. The Spanish language is a Romance language and is one of the aspects (including laws and general "ways of life") that causes Spaniards to be labelled a Latin people. Spanish has a significant Arabic influence in vocabulary; between the 8th and 12th centuries, Arabic was the dominant language in Al-Andalus[77] and some 4,000 words are of Arabic origin, including nouns, verbs and adjectives.[78] It also has influences from other Romance languages such as French, Italian, Catalan, Galician or Portuguese. Traditionally, the Basque language has been considered a key influence on Spanish, though nowadays this is questioned. Other changes are borrowings from English and other Germanic languages, although English influence is stronger in Latin America than in Spain.

The number of speakers of Spanish as a mother tongue is roughly 35.6 million, while the vast majority of other groups in Spain such as the Galicians, Catalans, and Basques also speak Spanish as a first or second language, which boosts the number of Spanish speakers to the overwhelming majority of Spain's population of 46 million.

Spanish was exported to the Americas due to over three centuries of Spanish colonial rule starting with the arrival of Christopher Columbus to Santo Domingo in 1492. Spanish is spoken natively by over 400 million people and spans across most countries of the Americas; from the Southwestern United States in North America down to Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost region of South America in Chile and Argentina. A variety of the language, known as Judaeo-Spanish or Ladino (or Haketia in Morocco), is still spoken by descendants of Sephardim (Spanish and Portuguese Jews) who fled Spain following a decree of expulsion of practising Jews in 1492. Also, a Spanish creole language known as Chabacano, which developed by the mixing of Spanish and native Tagalog and Cebuano languages during Spain's rule of the country through Mexico from 1565 to 1898, is spoken in the Philippines (by roughly 1 million people).[79]

Religion

Roman Catholicism is by far the largest denomination present in Spain,[80][81] although its share of the population has been decreasing for decades. According to a study by the Spanish Centre for Sociological Research in 2013 about 71% of Spaniards self-identified as Catholics, 2% other faith, and about 25% identified as atheists or declared they had no religion. Survey data for 2019 show Catholics down to 69%, 2.8% "other faith" and 27% atheist-agnostic-non-believers.[76]

Emigration from Spain

Outside of Europe, Latin America has the largest population of people with ancestors from Spain. These include people of full or partial Spanish ancestry.

People with Spanish ancestry

| Country | Population (% of country) | Reference | Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico: Spanish Mexican | 100,000,000 (>85%) | [2] | estimated: 30-40% as Whites 40-50% as Mestizos. |

| United States: Spanish American | 50,000,000 (16%) | [3] | 10,017,244 who identify themselves with direct ancestry from Spain.[82] 26,735,713 (53.0%) (8.7% of total U.S. population) Hispanics in the United States who identify as white (sometimes mixed with other European origins) or Mestizo via Latin America. |

| Venezuela: Spanish Venezuelan | 25,079,923 (90%) | [4] | 43% as white and 51% as mestizos. |

| Brazil: Spanish Brazilian | 15,000,000 (8%) | [5] | estimate by Bruno Ayllón.[83] |

| Colombia: Spanish Colombian | 39,000,000 (86%) [citation needed] | Self-description as "Mestizo, white and mulatto" | |

| Cuba: Spanish Cuban | 10,050,849 (89%) | [6] | Self-description as white, mulatto and mestizo |

| Puerto Rico: Spanish Puerto Rican | 3,064,862 (80.5%) | [7][84] [85][86] |

Self-description as white. 83,879 (2%) identified as Spanish citizens |

| Canada: Spanish Canadian | 325,730 (1%) | [87] | Self-description |

| Australia: Spanish Australian | 58,271 (0.3%) | [88] | Self-description |

The listings above shows the nine countries with known collected data on people with ancestors from Spain, although the definitions of each of these are somewhat different and the numbers cannot really be compared. Spanish Chilean of Chile and Spanish Uruguayan of Uruguay could be included by percentage (each at above 40%) instead of numeral size.

See also

- Demographics of Spain

- Hispanosphere

- Genetic history of the Iberian Peninsula

- Nationalisms and regionalisms of Spain

- Nationalities and regions of Spain

- Spanish nationalities and regional identities

- Languages of Spain

- Ancient peoples of Spain

- Peoples with Spanish ancestry

- Criollos (Spaniards in the former Spanish Empire)

- Afro-Spaniards

- Emancipados

- Fernandinos

- Latin Americans

- Latino Americans

- Isleños

- Louisiana Creole people

- Spanish Americans

- Spanish Argentinians

- Spanish Australians

- Spanish Brazilians

- Spanish Britons

- Spanish Canadians

- Spanish Central Americans

- Spanish Chileans

- Spanish Equatoguineans

- Spanish Filipino

- Spanish Mexican

- Spanish Peruvians

- Spanish Puerto Ricans

- Spanish Uruguayans

- Spanish Colombians

- White Latin Americans

Notes

- ^ a b Native names and pronunciations:

- Spanish: españoles [espaˈɲoles]

- Astur-Leonese: españoles (Extremaduran pronunciation: [ɛhpːaˈɲɔlɪh], Leonese pronunciation: [espaˈɲoles, -lɪs])

- Basque: espainiarrak [espaɲiarak] or espainolak [espaɲiolak]

- Aragonese: espanyols [espaˈɲols]

- Catalan: espanyols (Eastern Catalan pronunciation: [əspəˈɲɔls], Valencian pronunciation: [espaˈɲɔls])

- Galician: españois [espaˈɲɔjs, -ˈɲɔjʃ]

- Occitan: espanhòls [espaˈɲɔls].

References

- ^ a b "Official Population Figures of Spain. Population on 1 January 2013". INE Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Mexico – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ^ a b US Census Bureau 2014 American Community Survey B03001 1-Year Estimates HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY SPECIFIC ORIGIN Archived 12 February 2020 at archive.today retrieved 18 October 2015. Number of people of Hispanic and Latino Origin by specific origin(except people of Brazilian origin).

- ^ a b Resultados Básicos Censo 2011 Archived 13 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Brasil – España". hispanista.com.br. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Census of population and homes" (in Spanish). Government of Cuba. 16 September 2002. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ a b "Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000, Data Set: Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Explotación estadística del Padrón de Españoles Residentes en el Extranjero a 1 de enero de 2015" (PDF). Ine.es. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Estadística del Padrón de Españoles Residentes en el Extranjero (PERE) a 1 de enero de 2021" (PDF). Ine.es. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Padrón de Españoles Residentes en el Extranjero (PERE)". Ine.es. Archived from the original on 14 November 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ^ "Estadística del Padrón de Españoles Residentes en el Extranjero (PERE)a 1 de enero de 2024" (PDF). www.ine.es. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2024. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ "Padrón de españoles residentes en el extranjero. PERE. 1 de enero de 2022" (PDF). ine.es. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Estadística del Padrón de Españoles Residentes en el Extranjero (PERE) a 1 de enero de 2020" (PDF). Ine.es. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Padrón de españoles residentes en el extranjero. PERE. 1 de enero de 2022" (PDF). ine.es. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Padrón de españoles residentes en el extranjero. PERE. 1 de enero de 2022" (PDF). ine.es. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ [1] Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine 31 December 2014 German Statistical Office. Zensus 2014: Bevölkerung am 31. Dezember 2014 Archived 15 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ausländer in Deutschland bis 2019: Herkunftsland". De.statista.com. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "Padrón de españoles residentes en el extranjero. PERE. 1 de enero de 2022" (PDF). ine.es. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ "Spanish nationals population UK 2021". Statista.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "Padrón de españoles residentes en el extranjero. PERE. 1 de enero de 2022" (PDF). ine.es. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Explotación estadística del Padrón de Españoles Residentes en el Extranjero a 1 de enero de 2014" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ^ "La nueva emigración de españoles a Ecuador". Politicaexterior.com. 31 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Padrón de españoles residentes en el extranjero. PERE. 1 de enero de 2022" (PDF). ine.es. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ^ a b c "Censo electoral de españoles residentes en el extranjero 2009". Archived from the original on 27 January 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "Födelseland Och Ursprungsland". Scb.se. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "El número de españoles en Emiratos Árabes Unidos se duplica en sólo un año". www.abc.es (in Spanish). 15 October 2013. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "Embassy of Spain in Guatemala City, Guatemala profile. Guatemala" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Spain. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ "CSO Emigration" (PDF). Census Office Ireland. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ " Immigrant and Emigrant Populations by Country of Origin and Destination Archived 19 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Migration Policy Institute

- ^ "在留外国人の都道府県別ランキング!Youはどのくらい日本へ?" (in Japanese). 17 May 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ There are 3,110 immigrants from Spain according to INE, 1 January 2012, archived from the original on 3 March 2016, retrieved 13 May 2016

- ^ "Oficina del Censo Electoral / Cifras de electores". Ine.es. Archived from the original on 27 January 2010. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "ФМС России". Fms.gov.ru. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ "Embassy of Spain in Managua, Nicaragua profil e Nicaragua" (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Spain. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- ^ "Spain". 6 September 2022. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Tapiador, Francisco J. (2019). The Geography of Spain: A Complete Synthesis. Springer Nature. ISBN 9783030189075.

Catholicism is the nominal religion of most of the Spaniards

- ^ Boase, Roger (4 April 2002). "The Muslim Expulsion from Spain". History Today. 52 (4).

The majority of those permanently expelled settling in the Maghreb or Barbary Coast, especially in Oran, Tunis, Tlemcen, Tetuán, Rabat and Salé. Many travelled overland to France, but after the assassination of Henry of Navarre by Ravaillac in May 1610, they were forced to emigrate to Italy, Sicily or Constantinople.

- ^ "572 millones de personas hablan español, cinco millones más que hace un año, y aumentarán a 754 millones a mediados de siglo". Cervantes.es. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ a b c "Eurostat – Population in Europe in 2005" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Hallan una necrópolis fenicia en Osuna sin antecedentes en el interior de Andalucía". 24 April 2022. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Ethnographic map of Pre-Roman Iberia". Luís Fraga da Silva – Associação Campo Arqueológico de Tavira, Tavira, Portugal. Archived from the original on 11 June 2004. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

- ^ "Morisco – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "8 Masterpieces of Islamic Architecture". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ "Centro del Patrimonio Mundial". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "Palmeral de Elche - patrimoniomundial - Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte". Archived from the original on 16 January 2020.

- ^ Adams, Susan M.; Bosch, Elena; Balaresque, Patricia L.; Ballereau, Stéphane J.; Lee, Andrew C.; Arroyo, Eduardo; López-Parra, Ana M.; Aler, Mercedes; Grifo, Marina S. Gisbert; Brion, Maria; Carracedo, Angel; Lavinha, João; Martínez-Jarreta, Begoña; Quintana-Murci, Lluis; Picornell, Antònia; Ramon, Misericordia; Skorecki, Karl; Behar, Doron M.; Calafell, Francesc; Jobling, Mark A. (December 2008). "The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 83 (6): 725–736. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.007. PMC 2668061. PMID 19061982.

- ^ Vínculos Historia: The Moriscos who remained. The permanence of Islamic origin population in Early Modern Spain: Kingdom of Granada, XVII-XVIII centuries Archived 15 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine (In Spanish)

- ^ Axtell, James (September–October 1991). "The Columbian Mosaic in Colonial America". Humanities. 12 (5): 12–18. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ "Migration to Latin America". Let.leidenuniv.nl. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ a b c Ortega Pérez, Nieves (1 February 2003). "Spain: Forging an Immigration Policy". Migrationinformation.org. Archived from the original on 21 January 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "THE SPANISH OF THE CANARY ISLANDS". Personal.psu.edu. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Caistor, Nick (28 February 2003). "Spanish Civil War fighters look back". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ The Guardian (2 October 2019): 132,000 descendants of expelled Jews apply for Spanish citizenship Archived 7 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ BBC (8 October 2019): España y los judíos sefardíes: quién se beneficia de la decisión de ofrecer la nacionalidad a esta comunidad Archived 18 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei (11 June 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- ^ Posth, C., Yu, H., Ghalichi, A. (2023). "Palaeogenomics of Upper Palaeolithic to Neolithic European hunter-gatherers". Nature. 615 (2 March 2023): 117–126. Bibcode:2023Natur.615..117P. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05726-0. hdl:10256/23099. PMC 9977688. PMID 36859578.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gibbons, Ann (21 February 2017). "Thousands of horsemen may have swept into Bronze Age Europe, transforming the local population". Science. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Iberians - MSN Encarta". Encarta.msn.com. Archived from the original on 30 October 2009. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Álvarez-Sanchís, Jesús (28 February 2005). "Oppida and Celtic society in western Spain". E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6 (1). Archived from the original on 6 November 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Ethnographic Map of Pre-Roman Iberia (Circa 200 B". Arqueotavira.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2004. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Spain - History". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ a b Bycroft, Clare; Fernandez-Rozadilla, Ceres; Ruiz-Ponte, Clara; Quintela, Inés; Carracedo, Ángel; Donnelly, Peter; Myers, Simon (1 February 2019). "Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 551. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..551B. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08272-w. PMC 6358624. PMID 30710075.

- ^ a b Olalde, Iñigo; Mallick, Swapan; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Villalba-Mouco, Vanessa; Silva, Marina; Dulias, Katharina; Edwards, Ceiridwen J.; Gandini, Francesca; Pala, Maria; Soares, Pedro; Ferrando-Bernal, Manuel; Adamski, Nicole; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Cheronet, Olivia; Culleton, Brendan J.; Fernandes, Daniel; Lawson, Ann Marie; Mah, Matthew; Oppenheimer, Jonas; Stewardson, Kristin; Zhang, Zhao; Arenas, Juan Manuel Jiménez; Moyano, Isidro Jorge Toro; Salazar-García, Domingo C.; Castanyer, Pere; Santos, Marta; Tremoleda, Joaquim; Lozano, Marina; et al. (15 March 2019). "The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years". Science. 363 (6432): 1230–1234. Bibcode:2019Sci...363.1230O. doi:10.1126/science.aav4040. PMC 6436108. PMID 30872528.

- ^ "Les Wisigoths dans le Portugal médiéval: état actuel de la question". L'Europe héritière de l'Espagne wisigothique. Collection de la Casa de Velázquez. Books.openedition.org. 23 January 2014. pp. 326–339. ISBN 9788490960981. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ https://alpha.sib.uc.pt/?q=content/o-património-visigodo-da-l%C3%ADngua-portuguesa [dead link]

- ^ Quiroga, Jorge López (January 2017). "(PDF) IN TEMPORE SUEBORUM. The time of the Suevi in Gallaecia (411–585 AD)". Jorge López Quiroga-Artemio M. Martínez Tejera (Coord.): In Tempore Sueborum. The Time of the Sueves in Gallaecia (411–585 Ad). The First Medieval Kingdom of the West, Ourense. Academia.edu. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ James S. Amelang. "The Expulsion of the Moriscos: Still more Questions than Answers" (PDF). Intransitduke.org. Universidad Autónoma, Madrid. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Jónsson 2007, p. 195.

- ^ Adams, Susan M.; Bosch, Elena; Balaresque, Patricia L.; Ballereau, Stéphane J.; Lee, Andrew C.; Arroyo, Eduardo; López-Parra, Ana M.; Aler, Mercedes; Grifo, Marina S. Gisbert; Brion, Maria; Carracedo, Angel; Lavinha, João; Martínez-Jarreta, Begoña; Quintana-Murci, Lluis; Picornell, Antònia; Ramon, Misericordia; Skorecki, Karl; Behar, Doron M.; Calafell, Francesc; Jobling, Mark A. (12 December 2008). "The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula". American Journal of Human Genetics. 83 (6): 725–736. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.007. PMC 2668061. PMID 19061982.

- ^ Torres, Gabriela (31 December 2008). "El español "puro" tiene de todo". BBC Mundo. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Cervantes virtual: La invasión árabe. Los árabes y el elemento árabe en español Archived 27 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Adams SM, Bosch E, Balaresque PL, Ballereau SJ, Lee AC, Arroyo E, López-Parra AM, Aler M, Grifo MS, Brion M, Carracedo A, Lavinha J, Martínez-Jarreta B, Quintana-Murci L, Picornell A, Ramon M, Skorecki K, Behar DM, Calafell F, Jobling MA (December 2008). "The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 83 (6): 725–736. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.007. PMC 2668061. PMID 19061982.

- ^ "Diagnóstico social de la comunidad gitana en España" (PDF). msc.es. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ "Spain: Immigrants Welcome". Businessweek.com. 20 May 2007. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "National Institute of Statistics: Advance Municipal Register to January 1, 2006. provisional data" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Tremlett, Giles (26 July 2006). "Spain attracts record levels of immigrants seeking jobs and sun". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

- ^ a b "CIA – The World Factbook – Spain". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Arabic Contributions to the Spanish Language and Culture". Teachmideast.org. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ "The History of the Spanish Language" Archived 26 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine - The importance of this influence can be seen in words such as admiral (almirante), algebra, alchemy and alcohol, to note just a few obvious examples, which entered other European languages, like French, English, German, from Arabic via medieval Spanish. Modern Spanish has around 100,000 words Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Fennig, Charles D., ed. (2016). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Nineteenth ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ The National Catholic Almanac. St. Anthony's Guild. 1956.

- ^ Gannon, Martin J.; Pillai, Rajnandini (2015). Understanding Global Cultures: Metaphorical Journeys Through 34 Nations, Clusters of Nations, Continents, and Diversity. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781483340067.

- ^ Szucs, Loretto Dennis; Luebking, Sandra Hargreaves (1 January 2006). The Source: A Guidebook to American Genealogy. Ancestry Publishing. p. 361. ISBN 9781593312770 – via Internet Archive.

English US census 1790.

- ^ Más de 15 millones de brasileños son descendientes directos de españoles.

- ^ "Puerto Rico's History on race" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Puerto Rican ancestry" (PDF). p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2004. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Puerto Rican identity". Names.mongabay.com. 3 January 2013. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Ethnocultural Portrait of Canada Highlight Tables (2006 Census)". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 10 April 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

- ^ Statistics, c=AU; o=Commonwealth of Australia; ou=Australian Bureau of. "Redirect to Census data page". Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Sources

- Castro, Americo. Willard F. King and Selma Margaretten, trans. The Spaniards: An Introduction to Their History. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1980. ISBN 0-520-04177-1.

- Chapman, Robert. Emerging Complexity: The Later Pre-History of South-East Spain, Iberia, and the West Mediterranean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-521-23207-4.

- Goodwin, Godfrey. Islamic Spain. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1990. ISBN 0-87701-692-5.

- Harrison, Richard. Spain at the Dawn of History: Iberians, Phoenicians, and Greeks. New York: Thames & Hudson, 1988. ISBN 0-500-02111-2.

- James, Edward (ed.). Visigothic Spain: New Approaches. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980. ISBN 0-19-822543-1.

- Jónsson, Már (2007). "The expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain in 1609–1614: the destruction of an Islamic periphery". Journal of Global History. 2 (2): 195–212. doi:10.1017/S1740022807002252. S2CID 154793596.

- Thomas, Hugh. The Slave Trade: The History of the Atlantic Slave Trade 1440–1870. London: Picador, 1997. ISBN 0-330-35437-X.

- The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years (Science, 15 March 2019, Vol. 363, Issue 6432, pp. 1230-1234)